Immersive Ideas Founder Sarah Morris explores how ‘immersive’ emerged as a practice and methodology, not just a passing trend, but a cultural shift shaped by decades of experimentation.

The word immersive is now everywhere in the live experience industry. It appears across theatre, exhibitions, themed entertainment, festivals, brand activations, and cultural events. Yet its widespread use often obscures the fact that immersive is not a new idea, nor a shallow one. It is a term with a long, contested, and deeply theatrical history, and much much more than just a buzz word.

Immersive did not begin as a marketing label. It emerged through artistic experimentation, theoretical debate, and a growing dissatisfaction with distance between audiences and performance. While many disciplines have contributed to immersive practice, it was actually theatre that crystallised immersive as a cultural movement, articulated its values, and pushed it into the mainstream consciousness.

This article traces the history of immersive practice across theatre and live experience, arguing that immersive is not defined by technology or format, but by a convergence of artistic integrity, world building, audience journey and agency, story, performance, and theatrical design.

Immersion existed long before immersive had a name.

Before immersive became a recognised practice, performance was already concerned with how audiences enter a world rather than simply observe it. Classical theatre traditions were built around proximity, ritual, and shared focus. Greek tragedy used architecture, chorus, rhythm, and repetition to draw audiences into a collective emotional state. Medieval mystery plays moved through streets and civic spaces, embedding story into daily life and collapsing the distance between performance and reality.

Theatre scholar Dr Emma Cole notes that immersion has “intrigued humanity since antiquity,” pointing to the long standing human fascination with belief, illusion, and participation.

The impulse behind immersive work, the desire to step inside a story, to feel present within it, predates any contemporary terminology.

What emerges here is immersive as a practice not a label, it relies on trust, belief, and the willingness of audiences to enter into a world together. These principles sit at the heart of even the most mainstream immersive work today.

Although immersive thinking exists across many disciplines, it was theatre that transformed immersion from a design technique into a cultural force.

Experimental practitioners rejected the safety of the proscenium and began designing worlds audiences had to enter physically and psychologically. Immersion in theatre was never about comfort. It was about proximity, vulnerability, and consequence.

This is why immersive theatre became a movement, rather than simply a style. It was accompanied by critical writing, artistic intent, and cultural debate. Theatre gave immersion its intellectual backbone.

Alongside theatrical experimentation, theme parks and attractions had been developing immersive environments for decades. Dark rides, walkthrough attractions, and themed lands relied on coherent world building, scenic design, sound, smell, pacing, and audience flow to sustain belief.

Attractions understood something fundamental early on. Immersion depends on consistency. Worlds must operate according to internal logic. Set building, sightlines, operational choreography, and performance all reinforce narrative integrity.

What distinguishes attractions is scale, repeatability, and operational discipline and in contrast what distinguishes theatre is intent, intimacy, and liveness.

The most powerful immersive experiences today draw from both traditions, blending theatrical meaning with the spatial intelligence of attractions design.

The term immersive theatre enters academic discourse in the early 2000s as scholars attempt to name practices that resisted existing categories such as site specific, promenade, or participatory theatre, and naturally around a decade later, marketing terminology.

Dr Gareth White defines immersion as a perceptual and psychological state shaped by spatial orientation and attention.

Dr Josephine Machon emphasises embodiment and audience journey.

Language evolves because practice evolves. Immersive is not a perfect word, but it is a useful one. It sets expectations. It signals intent. It allows different disciplines to speak to one another.

To quote Joe Lycett, “not everything is immersive” But that does not invalidate the term. Language evolves alongside practice. Immersion exists on a spectrum, the word will continue to stretch as the work itself stretches.

Anger at the word immersive often masks discomfort with its popularity. But popularity does not negate legitimacy. It confirms cultural relevance. Don’t call something immersive just to sell tickets, but don’t be trapped by terminology either.

As Cambridge Dictionary quotes “IMMERSIVE – seeming to surround the audience, player, etc. so that they feel completely involved in something”

Language in the arts shifts as practice shifts, and as work needs to be communicated, words spread when they are needed.

For many audiences, immersive theatre became culturally legible through the work of Punchdrunk. Their productions introduced large scale environments, fragmented narratives, and audiences who moved freely through performance worlds rather than sitting passively in front of them. Theatre became the vehicle that carried Immersive into the mainstream.

Punchdrunk did not invent immersive theatre. They would be the first to acknowledge that. In fact, they now more often describe their work as site-responsive rather than immersive. What they did do was translate experimental practice into a form that captured public imagination at scale.

Immersive became something audiences could recognise, seek out, and pay for. Theatre made immersive visible.

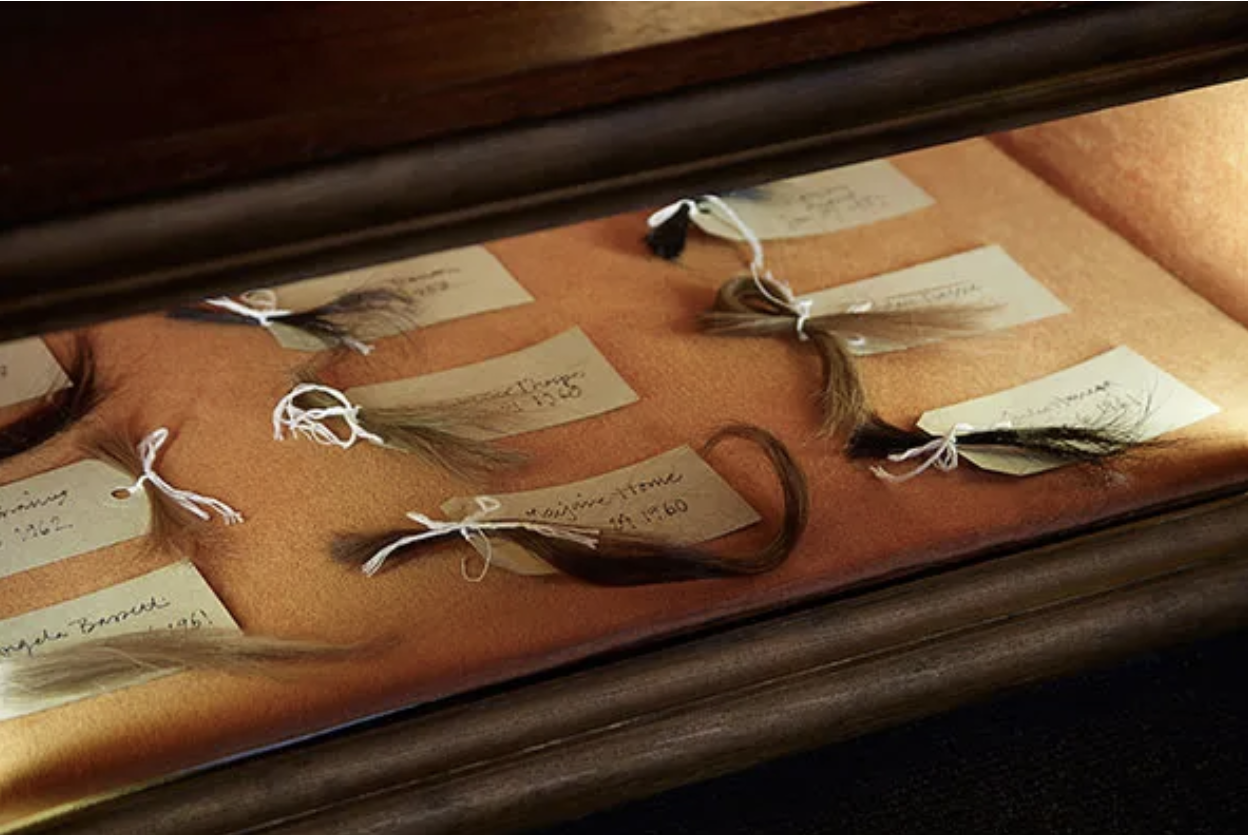

Alongside this sat a rich ecosystem of UK companies making immersive, interactive, and participatory work throughout the 2000s, long before immersive became a mainstream label. You Me Bum Bum Train, Shunt, Les Enfants Terribles, Secret Cinema, Coney, DifferenceEngine, CoLab Theatre, Apocalypse Events, dreamthinkspeak, Blast Theory, Uninvited Guests, Third Angel, Improbable, Rotozaza, Invisible Circus, Lab Collective, Dank Parish, and many others were already experimenting with audience agency, world building, participation, and non theatrical space, this is also where a lot of the current practitioner (including myself) who have gone on to make more commercial experiences cut their teeth.

This list is far from exhaustive. It exists as a reminder that immersive practice is not new. It is rooted in decades of experimentation, often happening in warehouses, abandoned buildings, churches, shops, offices, basements, and outdoor sites, almost never on a traditional stage. These pioneers laid the groundwork for everything that followed.

In contrast to those early days, immersive experiences now operates at scale. Ticketing platforms have reported sharp rises in demand, with Eventbrite recording an 83 percent increase in searches for immersive experiences year on year, and DesignMyNight reporting an 88 percent rise in interest. The global immersive entertainment market has been valued at £98 billion – The Independent, pointing to sustained public appetite rather than fleeting novelty.

With that growth comes friction. The word immersive is now used widely, sometimes loosely, and sometimes badly. Misuse can be damaging, not because the term itself lacks meaning, but because poor delivery erodes audience trust and undervalues the craft behind the work.

The much publicised failed Wonka experience is a useful example. It was marketed as immersive because that was the intention. Tickets sold for a reason. Audiences wanted to believe in the promise. The failure was not the ambition, nor the terminology, but the absence of expertise, structure, and understanding needed to deliver immersive in practice.

The risk to the industry is not that immersive is used too broadly. Projection mapped digital art in a gallery space has every right to call itself immersive. So do theatre, live events, attractions, and hybrid digital worlds. The real risk is the wrong people making the work without the skills, experience, or long term practice required to support it.

Immersive is not the problem. Inexpert delivery is, or the work being created without intent as a money grab, but this shouldn’t tarnish the industry or the word immersive.

And The Stage rightly observed that “the term immersive has been maligned and misinterpreted but it is still the word under which some of the most exciting theatre is being made.”

Immersive went mainstream because people wanted it. The responsibility now is to make it well.

Immersive is not a genre. It is a methodology.

At its core, immersive practice brings together artistic integrity, world building, audience journey, story, performance, theatrical design, and craft-led making. Sometimes this is supported by advanced technology, sometimes it is entirely analogue. When these elements align with intention, immersion is not applied, it emerges.

What has changed in recent years is scale, support, and reach. Immersive is no longer operating at the margins. It is now underpinned by formal funding streams and strategic investment, including national initiatives such as Immersive Arts UK, alongside long established public funders like Arts Council Engand. This has enabled artists and companies to develop original IP, experiment, tour, build sustainably, and take creative risks that would previously have been inaccessible.

At the same time, rapid advances in technology have expanded what immersive can be. Spatial audio, real time engines, mixed reality, projection mapping, responsive environments, and networked digital platforms have allowed immersive work to exist beyond physical sites, opening up digital and hybrid spaces that are participatory, persistent, and globally connected. Audiences can now step into worlds that live online, overlap with physical environments, or evolve over time, often at a fraction of the cost of traditional large scale builds.

Alongside funding and technology sits a growing professional ecosystem. Communities such as The Immersive Experience Network and World Experience Organisation have helped formalise knowledge sharing, advocacy, skills development, and international collaboration. This matters as it creates clearer career pathways, supports freelancers and small studios, and continues to generate new roles across design, production, performance, fabrication, engineering, and digital development.

The question is not whether a term is used imperfectly, but whether the work behind it is intentional, crafted, and coherent, when it does it remains a meaningful way to describe work rooted in world building, audience journey, and lived experience rather than novelty alone. We may never all agree on the terminology, but the trajectory is clear: immersive is a practice and what it describes is real, growing, and here to stay.

This is not a phase. It is a movement.

Immersive Experience Network: IEN Summit 2024

Immersive Ideas Ltd is not a name we arrived at casually. We own it because we have spent over a decade living and breathing the work that defines it, in it’s simplest form putting audiences inside experiences, not just in front of them.

Our practice has been built through making immersive work across theatre, live events, festivals, attractions, brands, and experiential environments, long before the term became widely used. Through this we have learned what immersive actually demands when real people are present, moving through space, making choices, trusting the world around them, and responding in real time.

Our skills come from doing the work. From testing audience behaviour, designing and building spaces that have to hold together under pressure, and making creative decisions that balance emotion, logistics, safety, scale, budget, and meaning.

We understand immersive because we have built it, broken it, refined it, and built it again, often in the strangest of spaces, often under tight constraints of budget, time, and circumstance.

Our past experience has given us a strong instinct for emotional logic, clear audience journey, and the subtle mechanics of trust. We know what audiences want, what clients and collaborators need, and how to design experiences that feel generous, coherent, and alive. This kind of thinking only comes from long term, hands on immersive practice.

We use the word immersive with care because it accurately describes the work we specialise in – If a project is not immersive in nature, in some form or another, it is probably not the right fit for us, and that clarity is deliberate and honest.

If you want to work with people who understand where immersive practice comes from and where it can go next, we would genuinely love to talk.

You can explore more writing on immersive practice, world building, and immersive experience design on our website, or get in touch to discuss a project, collaboration, or commission.

Immersive is not about pulling audiences in. It is about building worlds, spaces, attractions, and live experiences that earn belief, establish trust, and reward curiosity.

When we say at Immersive Ideas Ltd “we make reality sweat” we really do mean it!

Sarah Morris of Immersive Ideas Ltd We don’t just run events, we build worlds. From pop-up parties to sprawling festivals, theatre to brand activations, we create immersive adventures that draw audiences in and stay with them long after the experience end

You need to load content from reCAPTCHA to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information